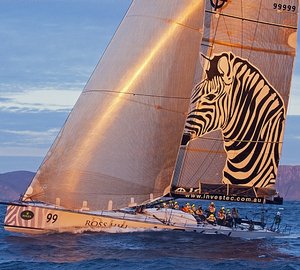

There are a hundred things happening at once. The light glancing off crystal water, a piercingly blue sky, perhaps the organ pipes of Tasman Island rearing out of the sea in the distance. The concentration of the man at the helm and the crew, perched wet and tired on the rail, or struggling to manhandle an acre of sail as the wind tries to tear it from their hands. The raw power of a big boat scything through a flat sea, or launching itself off foaming mountains.

It all comes together for a moment, barely a millisecond, for a photograph that will take you out onto that grand, heaving race track where ocean racers ply their trade.

Crew on Lahana cop spray during Rolex Sydney Hobart 2009 - Credit Dallas Kilponen, Courtesy of Fairfax Media

“I want to put the readers on board. To show them what it is like racing these boats out on the ocean,” says Fairfax photographer Dallas Kilponen, who has combined the role of photojournalist and crewman in five Rolex Sydney Hobarts.

His photos bring a rare intimacy to a sport that is mostly played out of sight, whether it is frantic drama in huge seas, or the eerie surrealism of a maxi yacht becalmed at dawn on a strangely motionless Bass Strait.

Kilponen is no passenger. He is big and strong, always a plus on a racing yacht, with a fine yachting pedigree.

“The first year I went down was in 2004, on the Volvo 60 Indec Merit. I took dad’s ashes on the boat to honour the old man. He was the navigator on Kialoa (the record breaking American maxi of the 1970s).

“We were forced to retire so it wasn’t until the next year, when I went down on the maxi Konica Minolta that I finally got to scatter some of his ashes on Constitution Dock.

“There are no free rides on these boats. I’m there as crew first, media second. My first priority is to race for the crew and to win. The best time to take photos is when there is a lot on, but when things are happening everyone has to be in synch. You can’t stop to take photos if it will wipe out the boat. So mostly I end up back up on deck with my camera when I am off watch, and hoping I can get a few hours sleep later.

“It can be awkward, though. There is a constant tension between when you are crew and when you can shoot.”

In 2006 Kilponen was on the New Zealand maxi Maximus when her giant mast came crashing down into the cockpit 20 miles off the New South Wales Coast, injuring several of her crew. “The first priority was making sure everyone was accounted for, triage, and only after everything was in order and the boat safe could I become a photographer.

“After a while the owner was saying that’s enough shots, but I said I’m here for the glory but I’m also a journalist.”

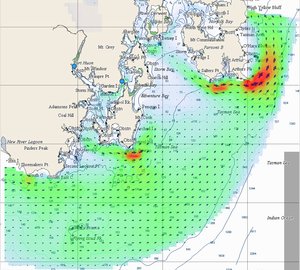

This will be Ian ‘Mains’ Mainsbridge’s 47th consecutive Rolex Sydney Hobart. The News Limited photographer does his best work from a helicopter, at times hovering meters from a yacht, thanks to the brilliance of ABCTV pilots Gary Ticehurst and Richard Powell, as it pounds down the course.

“We first used fixed wing aircraft in 1964. A single engine job for the start and then a twin engine plane so that we could follow the boats further out to sea. It was less expensive then. What we spent to cover a four day race then wouldn’t cover the start now.

“You have to have a very close relationship with your pilot,” he says. “We can only fly during daylight, so we are up at first light and don’t stop until 8pm or so at night. Then I have to file the photographs, and I might get to bed around 1100pm. Then it’s up at 4.30am to do it all again. It was easier when the boats were slower but these days it is hard to keep up, they cover so much distance during the night.

“But the pictures you get you can’t get anywhere else.”

Rolex photographer Daniel Foster covers the bulk of the race from both helicopters and small chase boats, or RIBs.

“The helicopters are like working in a big factory. The noise is exhausting,” he says, “but the helicopter allows you to change position very quickly, to move up and down and around the yacht, changing angles. It is so much harder from a RIB. With boats like Wild Oats XI being so fast you can be in the perfect position and three seconds later she has gone straight past you.

“I try to avoid nice postcard pictures,” Foster says. “I want to show what is happening out there, the atmosphere, the handling of the sails, the quick, perfect maneuvers. To show the difference between cruising and racing, and give a feeling for what it is like to compete in a wet, cold environment.”

For all three the thing that makes a great yachting photographer is anticipation.

“It’s understanding the sport, the weather, so you can predict when a boat is going to be in a predicament,” says Mainsbridge. “Taking the shot is the easy bit.”

“It’s about pre-empting what is about to happen,” Kilponen agrees, “so that you can position yourself to get the shot. You have to understand the boat, what is going to happen, then use the elements to get the shot you want.”

“You have to know in advance where they will go after they come around a mark so that you can be in the right place to see the faces of the crew, what they are doing. You don’t want to end up with just a pretty picture of big white sails,” says Foster.

“The best photos I have taken were when Koomooloo was sinking,” says Mainsbridge. “The blokes standing on deck. One was on the phone, others were bailing. Also the ones I took when the crew was abandoning Skandia. We were right down at the same height, looking at the blokes in the life raft. We could see their teeth.

“When you’re doing it you feel for the people but you have to get the picture. You know helicopters make a lot of noise and in emergencies people need to be heard. But it’s also true that the guys on Skandia waited until we got there before they abandoned her. We couldn’t rescue them in the chopper but we could guide the rescuers in.”

One of Forster’s most memorable shots is of the maxi Brindabella in a trough between two waves so huge only her tall mast and orange storm sail can be seen. He took it from a helicopter hovering in the adjacent trough.

“For five years there was one picture I always wanted to take,” says Kilponen, “of the guys sitting beside me on the rail. I wanted people to see the force of the spray and how punishing it is to be there hour after hour. Last year when a squall hit us, all my proper gear was down below so I held out a cheap little waterproof camera I keep in my pocket that never works.

“It’s my favorite shot.”